Alex Teboul-Profits Over Patient Health; Direct-to-Consumer Advertising of Prescription Medication

April 28, 2016 10:39 pmOver the past two decades, the American pharmaceutical drug industry has come under increasing pressure to reform its practice of advertising prescription medication to consumers.20,22 Critics argue that direct-to-consumer advertising, or DTCA, places patients at undue risk by motivating them to request prescriptions they do not need or are ill informed about.3,6,10 Remarkably, this practice is only legal in the United States and New Zealand.10,13 The case to reform the industry is further augmented by limited drug effectiveness5,9,11,, adverse drug reactions12, manipulative marketing tactics3,6, and unparalleled profit margins on drugs1,15. Moreover, the debate highlights the important issue of whether treating patient health as a lucrative business ultimately violates the industry’s ethical obligations. Upon further inspection, it will become evident that a decision to abolish the practice of direct- to-consumer advertising would represent a victory for the ethical treatment of American patients.

All members of the health care sector share equally in the responsibility and honor of preserving the public’s wellbeing. Consequently, physicians and pharmaceutical companies alike should be held to the strictest ethical standards. These standards depend on a core set of principles that must continue to drive health care professionals: Autonomy, Beneficence, Nonmaleficence, and Justice.21 Evaluating the relative merits and shortcomings of DTCA will therefore hinge upon its alignment with these core values.

Honoring a patient’s right to make their own decisions is to grant them Autonomy. When it comes to prescription medication, this philosophy can turn problematic. Often times, drug advertisements will hook consumers on the idea that they absolutely need a drug to lead the lives they want.6,22 This places the burden on physicians and pharmacists to use their expertise to reliably advance their patients’ health. Thus, this level of the health care sector has been tasked as the most direct upholders of Beneficence.

Unfortunately, due to profit- driven responsibility to investors, companies tend to overinflate drug effectiveness or provide inadequate alternative treatment options in studies.5,9 The resulting cases of patient harm from adverse drug reactions8 and financial stress from price markups of brand name medication3 could thus be considered neglectful of the Nonmaleficence clause. Likewise, it reveals major pharmaceutical companies as remiss toward Justice, by unfairly advancing a specific medication for reasons other than solely the public’s wellbeing.

Despite these critiques, it is important to remember that the pharmaceutical industry has contributed in positive ways to public health and the economy.17 Similarly, the vast majority of health care professionals have dedicated their lives to helping the lives of others. The discussion must remain mindful of the fine line between drugs that do a great deal of good and the profiteering of such drugs by large pharmaceutical companies.

I. Regulations on Direct-to- Consumer Advertising of Pharmaceuticals

II. Misleading Marketing Tactics

III. Economic Considerations

IV. What’s Next?

Regulations on Direct-to- Consumer Advertising of Pharmaceuticals

Before examining the effects of DTCA on public health and its success as a tool for pharmaceutical companies, a review of government regulations is necessary. The FDA plays the largest role in regulating this type of drug promotion.10 In 2008, the most extensive review of DTCA regulation in the United

States was compiled and published in the American Medical Writer’s Association Journal. It highlights the critical 1997 FDA Guidance on DTCA, which has allowed pharmaceutical companies to promote drugs via broadcast media.14 Regrettably, that specific regulation did not require advertisements to devote equal time to promotion and risks. Consequently, commercials generally spend more time attempting to win over consumers than warn them about the dangers a drug may pose.3,5,20

In response to concerns that the FDA regulations were inadequately protecting consumers, a new regulation was added in 2006 that requires manufacturers to at least provide clear and concise prescribing information.14 The challenge with this type of regulation is that prescribing information is typically dense with technical jargon more suitable for a health professional audience than the public.10 If the public’s best interests are the sole motivating factor in maintaining DTCA, then the FDA should more strictly require advertisements to provide effectiveness ratings and prescribing information in a manner that lay audiences can easily understand. That would be more in accordance with the industry’s ethical obligations to patients. Specifically, it would honor the trust patients have that their healthcare providers are doing their utmost to ensure their wellbeing. It would also respect the World Health Organization’s recommendation that the United States comply with international codes on the regulation of DTCA.24 Lacking strong evidence of a positive relationship between DTCA and facing condemnation from the international medical and legal communities for this practice, one can only conclude that the American pharmaceutical industry is more concerned with getting their products to market than upholding core ethical principles.

Another contentious issue is the bending of rules by ads to draw in larger audiences. The FDA Amendments Act of 2007 requires all broadcast ads to include important risk information in a “major statement”. Ads must also include either details on the drug’s prescribing information or sources for viewers to find more information.7 While the sentiment behind this legislation is positive, it still just an “adequate provision” requirement.7 Simply put, this regulation does not go far enough to protect patient interests. Getting a product claim ad to meet this requirement is as simple as tacking on a paragraph of fine print at the end of an otherwise misleading ad.

One counterpoint generally invoked to maintain the current regulations is that drug ads help get patients to seek treatment.6,9 Such claims are largely unsubstantiated and potentially misleading.9 This duplicity further compromises Big Pharma’s credibility as an ethically driven institution. Additionally, survey objectivity may be compromised by question phrasing. Asking if product claim DTC ads positively increase patient-physician interaction and if it is more effective than a help-seeking ad will yield two separate responses.9 While both are used to gauge the effectiveness of DTCA, help-seeking ads are more informative and likely to generate similar patient-physician discussion.14

Misleading Marketing Tactics

The ability of pharmaceutical companies to draw in new patients hinges upon the success of their advertisements. Through television, print, and Internet media sources, prescription medication advertisements pull in millions of patients with dubious psychological tactics.1,3,6 In 2013, an extensive study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine found that 57% of claims in drug advertisements were potentially misleading and 10% were entirely false.5 The table in Figure 1further summarizes their findings. With such staggering statistics available to the FDA, it is again surprising that more regulation has not been advanced.

Separate research published in the American Journal of Public Health 2010 detailed a more comprehensive plan to regulate DTCA and avoid misleading information being allowed into broadcast ads. One of the key recommendations of the plan is the addition of a clause requiring quantitative, substantive information about benefits and risks.9 It also pushes for ads to more clearly identify their target audience. This would prevent the widening of illness boundaries to expand user bases – thereby placing health improvement ahead of profits.9,13

Figure 1: Content Analysis of False and Misleading Claims in Television Advertising for Prescription and Nonprescription Drug [5]

Adding to the negative public and professional views on large drug company behavior, research has indicated that most new drugs, about 78%, are no better than existing medication in the market.3 Companies go to great lengths to extend patents and outcompete cheaper, generic alternatives.3,5 This raises the costs for patients and represents a fundamental breach of the core ethical principles guiding work in the healthcare profession. Putting business aside, the goal of any professional involved in healthcare is to provide the easiest access to quality, affordable care.

Advertisements also capitalize on the strategy of promoting lifestyles alongside their prescription drugs.6,11,20 Broadcast ads generally show smiling, happy people and upbeat, smooth music, without much substance related to the actual illness. These are tools that may potentially distract and manipulate viewers. Yet, these tactics may also reduce stigma and increase patient confidence to seek help.8,9 Realistically, it does the bare minimum to caution viewers on the risks associated. A list of horrible side effects listed in monotone over images of a happy, confident individual does more to draw in consumers than protect patients.

Economic Considerations

Between 1996 and 2004, investment into direct-to-consumer advertising of pharmaceuticals rose by approximately 500% in the United States.3 Adding to concerns of unethical conduct, studies have indicated that pharmaceutical companies can earn as much as 4 times their investment in advertising back with drug sales.3,19 For precisely this reason, Americans are constantly exposed to pharmaceutical ads.

Incredibly, the pharmaceutical industry consistently achieves profit margins that are only paralleled by the banking sector. Of the five largest industrial sectors, American pharmaceutical giants make the largest profit margins.1 In 2013, Pfizer made an unjustifiable 42% profit margin.1 For comparison, the highest bank margin was 29%. Even oil and gas margins were smaller, with a maximum margin of 24% in 2013.1 Such high margins on pharmaceutical drugs do a disservice to healthcare professionals who have dedicated their lives to ensuring patients are respected and treated fairly. The pharmaceutical industry should not aspire to parallel the banking sector, one of the most distastefully viewed sectors of our economy. When the public becomes aware of statistics like these, it breaks down trust in the system and ultimately exposes the fact that patients are being exploited.

To justify their massive profits, pharmaceutical companies tend to cite figures pointing to the high cost of creating new drugs.15,19 The most commonly referenced studies are those conducted by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. The most recent analysis detailed a cost of over 2.5 billion dollars to develop a new pharmaceutical drug and bring it to market.15 This represents a 145% rise in cost over the past 10 years.15 Other studies have contested these figures and even GlaxoSmithKline’s CEO, Andrew Witty, disputes the notion of a billion dollar development cost.25 Rohit Malpani, Director of Policy and Analysis for Doctors Without Borders, has publicly criticized figures that far overestimate the cost of drug development. He contends that the true cost of drug development is less than 200 million dollars.25

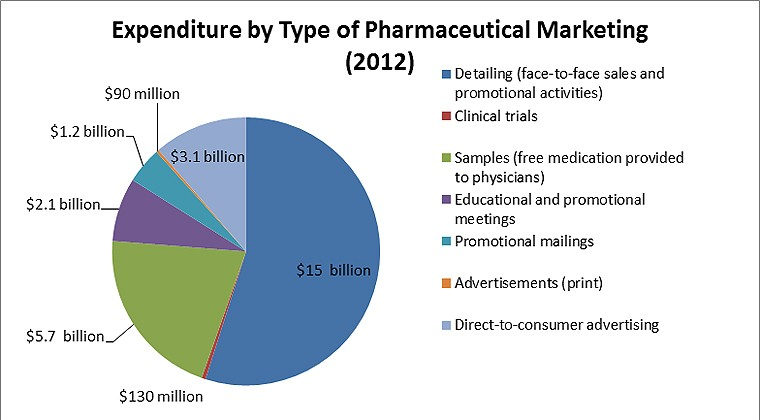

Figure 2: PewTrusts.org. Original Source: Cegedim Strategic Data, 2012 U.S. Pharmaceutical Company Promotion Spending (2013) [16]

While the focus of this paper is DTCA of prescription medication, it is import to also mention the incredible sums pharmaceutical companies invest into other forms of marketing. The figure above details 2013’s industry expenditures. Importantly, it brings to light the approximate 24 billion dollars spent annual on the direct and indirect marketing of drugs to physicians.16

Considering the impact of the industry on the U.S. economy must also consider all the various forms of employment provided. Estimates place the U.S. biopharmaceutical sector employment number at over 810,000, while simultaneously supporting 3.4 million jobs across the country.17

The question becomes, is DTCA ethical if profiteering off medication creates a net gain for the livelihood of American citizens? Restricted to the core principles of Autonomy, Beneficence, Nonmaleficence, and Justice, the answer is still no. Clearly that any gains to the public by profiting heavily off of illness still constitute an ethical failure of the system. Other developed nations have smaller pharmaceutical sectors with higher health standards that the U.S., indicating that public health may not even be greatly advance by a large pharmaceutical sector.3

What’s Next?

If the pharmaceutical drug industry is serious about ethically preserving public health it needs to reform, and do so quickly. Especially at a time when the United States healthcare system is in such a state of flux, remedying the problem of DTCA should be feasible. Stricter regulation or the complete restriction of DTCA for prescription medication would be in the best interests of the public. Opponents who argue that this would have negative impacts on public health should consider that currently, the U.S. ranks last in terms of quality and efficiency of healthcare.4 Perhaps, if the United States complied with international regulations of DTCA, some of the causes of this poor ranking could be ameliorated. Also, the cost of health care per person in 2011 was roughly $8,508, more than double that of the top ranked system in the U.K.4 If companies invested more into increasing R&D efficiency and reduced DTCA, costs would likely go down.

When pharmaceutical companies place profits above patient interests they do a dishonor to the hardworking medical professionals who have dedicated their lives to protecting the common good. Simultaneously, they are taking advantage of the trust consumers have placed in the healthcare system. With adverse drug reactions to prescription medications being involved in as many as 100,000 deaths annually. This statistic factors in prior health conditions, but it demonstrates the scope of potential adverse drug reactions. When emergency hospitalizations in the tens of thousands annually, awareness of this issue should be extended beyond the medical community. 3,19 Cases like the Vioxx scandal and abuse of promoted SSRI’s should not remain the status quo.3,9,19 Many advertised drugs like Aleve, do not adequately warn users to consult with medical professionals before use. The result is patients concluding they are safe, when really they run the risk of kidney failure.

So how can pharmaceutical companies be more ethical? A moral spending distribution for large pharmaceutical companies would contribute to public health beyond tightening the effectiveness of drugs and reducing misleading ads. With such massive profits, companies could improve access to healthcare. They could also develop nutritional and exercise programs to target audiences they currently attract with ineffective pills. At the same time, they could lower the drug costs on medication that is of incredible benefit to survival like cancer drugs. It is important to note that other countries have succeeded in maintaining the health of their citizens with far smaller pharmaceutical sectors. Canada and many European countries do far better than the United States on a series of healthcare rankings, all without DTCA and large pharmaceutical sectors. The FDA should immediately ban DTCA, as it is unethical. It serves to exploit patients for profit, while breaking trust and neglecting the ethical responsibilities of the healthcare industry to the public.

References

Anderson R. Pharmaceutical industry gets high on fat profits – BBC News. BBC News. 2014. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/business-28212223. Accessed September 8, 2015.

Apha.org. America's Health Rankings 2014. 2014. Available at: https://www.apha.org/news-and-media/news-releases/apha-news-releases/health-rankings- 2014. Accessed September 13, 2015.

Big Bucks, Big Pharma: Marketing Disease And Pushing Drugs. Ronit Ridberg; 2006.

Commonwealthfund.org. US Health System Ranks Last Among Eleven Countries on Measures of Access, Equity, Quality, Efficiency, and Healthy Lives. 2014. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/press-releases/2014/jun/us-health-system- ranks-last. Accessed September 9, 2015.

Faerber A, Kreling D. Content analysis of false and misleading claims in television advertising for prescription and nonprescription drugs. – PubMed – NCBI. Ncbinlmnihgov. 2014. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24030427. Accessed September 9, 2015.

Fain K, Alexander G. Mind the gap: understanding the effects of pharmaceutical direct- to-consumer advertising. – PubMed – NCBI. Ncbinlmnihgov. 2014. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24848202. Accessed September 10, 2015.

Fda.gov. Basics of Drug Ads. 2015. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/PrescriptionDrugAdvertising/ucm0 72077.htm. Accessed September 11, 2015.

Fda.gov. Preventable Adverse Drug Reactions: A Focus on Drug Interactions. 2014. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/DrugIntera ctionsLabeling/ucm110632.htm. Accessed September 15, 2015.

Frosch DL, Grande D, Tarn DM, Kravitz RL. A decade of controversy: balancing policy with evidence in the regulation of prescription drug advertising. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):24-32.

Furberg C, Furberg B, Sasich L. Knowing Your Medications: A Guide To Becoming An Informed Patient. Express Scripts Holding Company; 2015:184-188.

Lo C. Big pharma and the ethics of TV advertising – Pharmaceutical Technology. Pharmaceutical-technologycom. 2013. Available at:

http://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/features/feature-big-pharma-ethics-of-tv- advertising/. Accessed September 15, 2015.

Lovegrove M, Mathew J, Hampp C, Governale L, Wysowski D, Budnitz D. Emergency Hospitalizations for Unsupervised Prescription Medication Ingestions by Young Children.PEDIATRICS. 2014;134(4):e1009-e1016. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0840.

Mercola D. Only 2 Countries Permit DTC Ads – The US is One of Them. Mercolacom. 2012. Available at: http://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2012/07/16/drug- companies-ads-dangers.aspx. Accessed September 10, 2015.

Mogull S. Chronology of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising Regulation In The United States.American Medical Writers Association. 2008;23(3):106-109. Available at: http://www.amwa.org/files/Journal/2008v23n3.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2015.

Mullin R. Cost to Develop New Pharmaceutical Drug Now Exceeds $2.5B. Scientific American. 2014. Available at: 16. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/cost-to-develop- new-pharmaceutical-drug-now-exceeds-2-5b/. Accessed September 13, 2015.

Pewtrusts.org. Persuading the Prescribers: Pharmaceutical Industry Marketing and its Influence on Physicians and Patients – Pew Charitable Trusts. 2013. Available at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2013/11/11/persuading-the- prescribers-pharmaceutical-industry-marketing-and-its-influence-on-physicians-and-patients. Accessed September 15, 2015.

Phrma.org. The Economic Impact of the Pharmaceutical Industry. 2015. Available at: http://www.phrma.org/economic-impact. Accessed September 15, 2015.

Pollack A. F.D.A. Approves Addyi, a Libido Pill for Women. Nytimescom. 2015. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/19/business/fda-approval-addyi-female- viagra.html. Accessed September 19, 2015.

ProCon.org. Prescription Drug Ads. 2014. Available at: http://prescriptiondrugs.procon.org/. Accessed September 17, 2015.

Ventola C. Direct-to-Consumer Pharmaceutical Advertising: Therapeutic or Toxic?. Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2011;36(10):669. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3278148/. Accessed September 9, 2015.

Vtethicsnetwork.org. Vermont Ethics Network. 2015. Available at: http://www.vtethicsnetwork.org/ethics.html. Accessed September 8, 2015.

Wang B, Kesselheim A. The Role of Direct-to-Consumer Pharmaceutical Advertising in Patient Consumerism. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(11):960-965. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.11.pfor1-1311.

Woolf S, Aron L. U.S. Health In International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. The National Academies Press; 2013:21-23.

World Health Organization. Direct-to-consumer advertising under fire. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/8/09-040809/en/. Accessed September 10, 2015.

Malpani R. R&D Cost Estimates: MSF Response to Tufts CSDD Study on Cost to Develop a New Drug. MSF USA. 2014. Available at: http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/article/rd-cost-estimates-msf-response-tufts-csdd- study-cost-develop-new- drug?utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook&utm_campaign=social. Accessed September 19, 2015.

Categorised in:

This post was written by Admin3